AVIF is a complex image format with a lot of potential. A significant amount of this potential was unlocked in 2024; Gianni Rosato, our founder and contributor to these efforts, details how this was done & talks about the future of modern image codecs on the Web.

Introduction

AVIF (AV1 Image File Format) is growing in popularity for web images, thanks to its impressive compression and quality. However, open-source AVIF encoders struggled with consistency, usability, and overall compression efficiency for a long time due to their development cycles and (inherently) the way video encoders are designed.

My name is Gianni Rosato, the founder of Halide Compression. My compression background has a foundation in working on the SVT-AV1 project with Meta as well as working with Two Orioles, the main authors behind the dav1d software AV1 decoder. My journey began with founding the SVT-AV1-PSY project, aimed at providing a community-developed enhanced SVT-AV1 encoder for perceptual quality. One of the things I worked on while involved with SVT-AV1-PSY was considerably improving the state of the art for AVIF.

Why AVIF?

AVIF wasn't on our radar as video encoder developers, but a community member suggested we try it out and we saw promising results instantly with our existing featureset. This prompted us to begin escalating our focus on still images; as a community-built open source project, we were not beholden to the interests of companies that only derived value from our video work, so we were able to shift focus without much trouble.

This is something I want to highlight up front in this blog post: modern image codecs on the Web tend to be derivations of video standards (e.g. WebP images being VP8 keyframes, same with HEIC/HEVC as well as AVIF/AV1) with reference and production encoders designed for video. Because of this, image encoding is a poorly considered externality (with the exception of WebP, which has an image-first reference library separate from libvpx in the form of libwebp).

This is where the Web ecosystem is headed; build powerful video encoders with associated image formats, and hope that being good at video means images will benefit. This is usually effective, but to truly unlock value in these formats, boutique image-first design considerations are necessary. This became more clearly true as I continued to work on AVIF in SVT-AV1-PSY.

Design Overview

Improving still picture AVIF encoding (ignoring animations, which are essentially videos after all) means improving all-intra coding. In video terminology, intra-coded frames are frames which do not reference data from other frames (they are standalone pictures).

"Tune Still Picture" (also called "Tune 4") delineates SVT-AV1-PSY's intra-optimized compression mode, differentiating it from the other tuning options in the encoder.

Tune Still Picture is comprised primarily of the following techniques under the hood:

- A quantization matrix scaling curve

- Deblocking loop filter sharpness adjustment

- More sensitive variance-adaptive quantization

- Photography-tuned variance-adaptive quantization scaling

- A custom screen-content detection algorithm

- Modifications to lambda weight modulation

These techniques were the primary contributors to Tune 4's strength in metrics as well as perceptual quality. I'll explain what each option does in more detail below.

1. Quantization Matrix Scaling

After a frame is transformed from the spatial domain to the frequency domain (a process that separates a group of pixels into different frequency components), a quantization matrix (QM) is applied. This matrix contains different scaling factors for various frequencies. By using a non-uniform quantization matrix, an encoder can specify different levels of quantization to different frequency components (e.g. low versus high-frequency), which may allow for more graceful degradation according to the human eye as data is discarded.

The AV1 specification includes a set of 15 predefined QMs. Encoders can select one of these for luma (light) and chroma (color) in each frame. AV1's predefined QMs are designed to be reasonably effective for a wide range of content. SVT-AV1-PSY enables QMs by default for better visual quality, and specifies a QM range that the encoder can use when encoding a video.

For still images, we care less about QMs over time and more about how carefully choosing QMs during the encoding process for a single intra-coded frame (our image). In order to identify the best QMs for our use case, we used an industry-standard image dataset (the CID22 Validation Set) and measured a convex hull (how quality changes relative to size) according to the SSIMULACRA2 image quality metric for each QM.

We found that for different quality levels, on average, different QMs performed better. We selected the best QMs for each range in order to achieve the best overall convex hull.

2. Deblocking Loop Filter Sharpness

This was a simpler change, despite being potentially the most effective.

SVT-AV1-PSY features user-facing controls to modify the encoder's internal deblocking loop filter sharpness. AV1 divides video frames into blocks in order to compress different regions of a frame differently. The deblocking loop filter in an encoder controls how the boundaries between blocks in each frame are smoothed into one another, and can be modified to be smoother or sharper depending on internal controls.

We tried each sharpness level on a convex hull (as we did with QMs) and landed on the best overall level to set as the default for Tune Still Picture. This particular case illustrates the difference between an image encoder and a video encoder. While smoother deblocking might help a video encoder by potentially improving inter-frame consistency and leading to better compression, working with a single frame tells a different story. Thus, an image encoder ends up making drastically different decisions than a video encoder, even with the same set of tools.

3. Variance-Adaptive Quantization Sensitivity

Variance Adaptive Quantization (VAQ) is a feature that comes from the x264 days, helping to drastically improve visual quality while also improving metrics due to the nature of quantization in the face of low-variance image data (this explainer by Julio Barba, the author of VAQ in SVT-AV1(-PSY), is a very good guide on how it works).

VAQ only makes an encoder better when it is used properly. In the case of still images, increasing the strength of VAQ helped improve our convex hull, but the changes to VAQ didn't stop there.

4. Variance-Adaptive Quantization Scaling

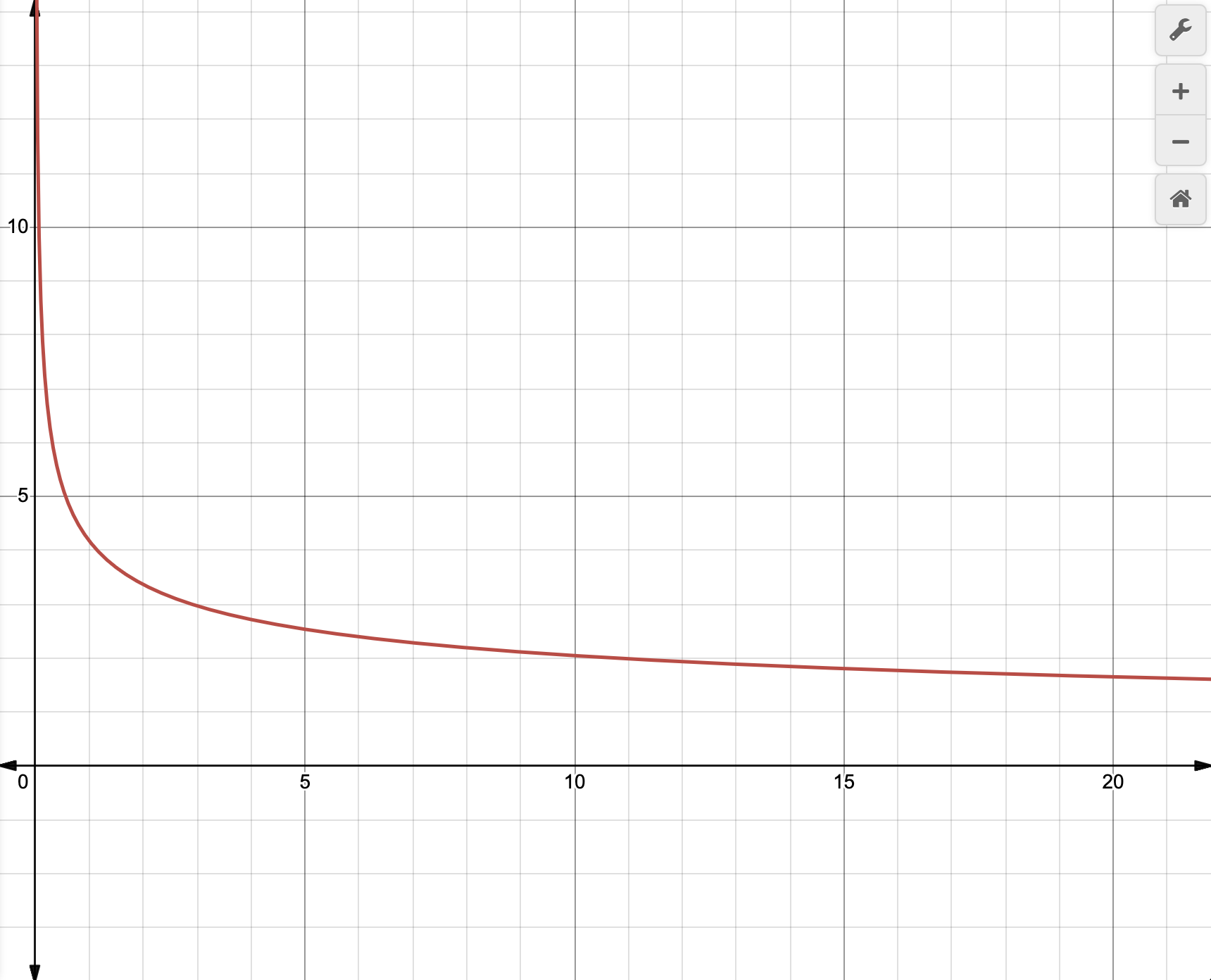

The scaling algorithm for the default VAQ implementation in SVT-AV1 follows this equation:

q = pow(1.018, strengths[strength] * (-10 * log2((double)variance) + 80))

If we take strength as a configurable variable instead of a look-up table for the sake of demonstration, we can plot a curve that looks like this:

The shape of this curve should generally illustrate how variance adaptive quantization works, if we think about the x-axis as our input variance value and our y-axis as our returned quantization scaling value. Less variance means we "boost" the amount of bits sent to an area to improve its quality.

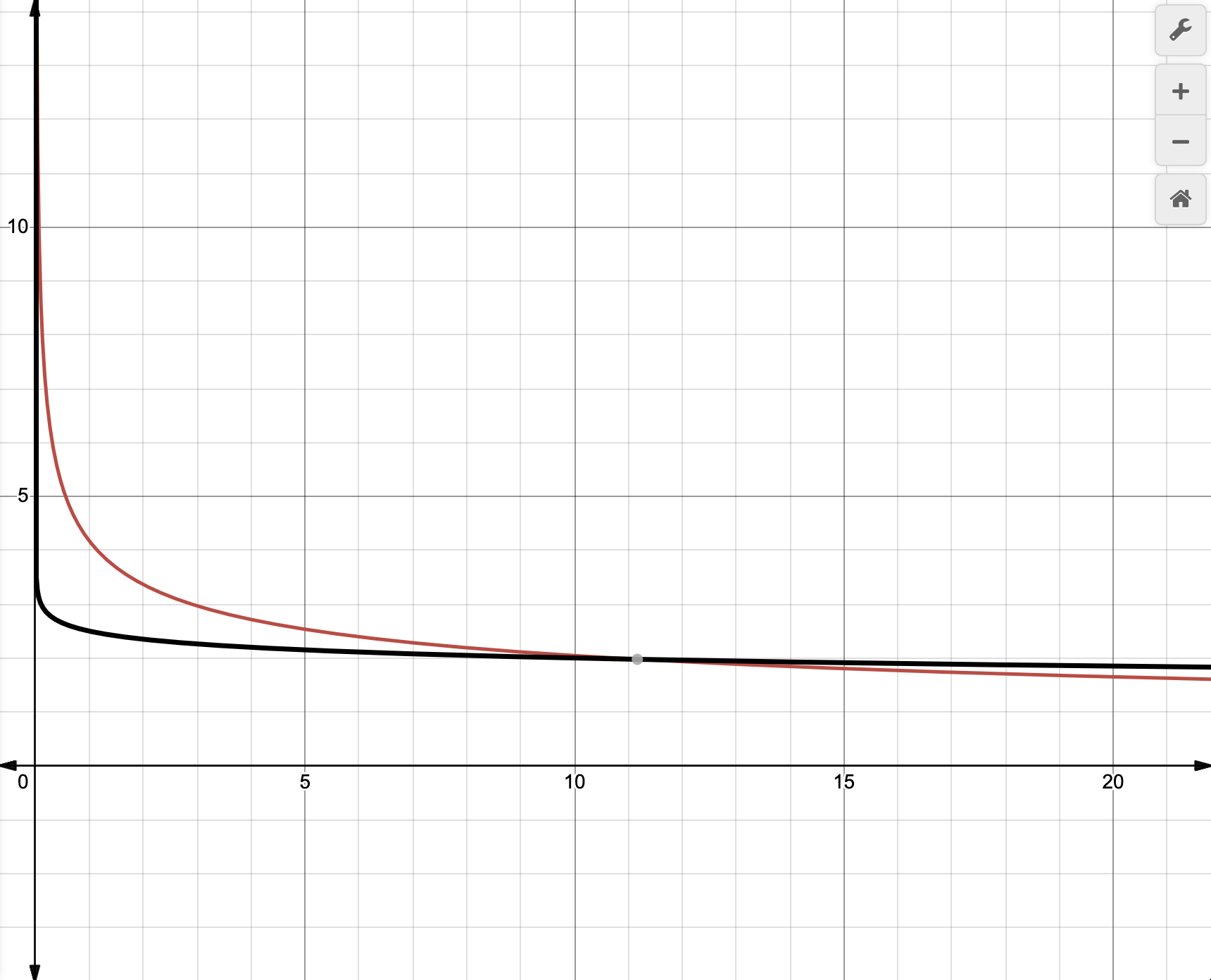

Tuning for photographic content meant using a modified curve, defined by the following equation:

q = 0.15 * strength * (-log2((double)variance) + 10) + 1;

Here is the associated visual, with the black line representing the Still Picture curve:

Finding this curve required considering the type of data present in photographs, the sensitivity of quality to quantization in intra-coded frames, and how our convex hull responded. One interesting thing about this curve is that while low-variance data isn't boosted as eagerly, higher variance data is tapered back much more slowly.

5. Screen Content Detection

AV1 happens to have some special tools (namely Intra Block Copy/IBC & palette mode) that help immensely with non-photographic "screen content" (e.g. text screenshots, lineart, digital drawings) when compared to photographs.

Making screen content tools useful was accompanied by the goal of generally better internal tuning when facing screen content. However, in order to improve efficiency on screen content, you need to know when you're encoding it. The default screen content detection algorithm in SVT-AV1 wasn't effective for our use case, so we worked on engineering a new one.

Julio & I both came up with separate implementations, and Julio's ended up being our choice of implementation in the end. Reference Zig code is provided if you want more technical details, but the algorithm is able to detect screen content effectively as well as differentiate between different kinds of screen content. There is a basic classification, as well as high-variance, medium confidence, and high confidence. This implementation allowed us to strengthen an already strong use case for AVIF, where older codecs (namely JPEG) fell short.

6. Lambda

The lambda is a parameter used in rate-distortion optimization (RDO). RDO is the process by which an encoder decides the best way to encode a block of pixels by evaluating a cost function that balances two competing goals. These goals are minimal distortion (how much the encoded block differs from the original) and minimal rate (how much data is required to encode a block). Lower rate means a smaller file. The RDO cost function is typically expressed via the equation below.

Cost = Distortion + λ * Rate

Due to the nature of this very simple equation, you can see that a high lambda prioritizes rate reduction while a lower lambda will favor reducing distortion.

In simple terms, what Tune Still Picture does is modulate the lambda depending on the amount of quantization we desire. At higher and lower quantization (the lowest & highest ends of the quality spectrum respectively), we ramp down the lambda. In the middle, we ramp it up. This improved our convex hull.

Aftermath

The result of Tune Still Picture was up to 15% better compression for AVIF, as well as significantly better consistency and greater flexibility for SVT-AV1 as our features are merged (this is still an ongoing effort). See for yourself on the SVT-AV1-PSY AVIF page. The effort for better still image performance with SVT-AV1 also involved reducing the minimum size supported by the encoder to below 64x64 as well as implementing support for odd dimensions.

Eventually, the bulk of our Tune Still Picture changes were merged into libaom's aomenc, the reference AV1 encoder developed by Google. They live on as aomenc's tune iq (for "image quality") and our gains are still visible there.

The results above were achieved on the Kodak True Color image dataset on libaom v3.12.1 via libavif.

What Now?

Now you know the gist of our still image improvements for AVIF! Researching & building open-source image encoding improvements was fun, but the future may look different for image codecs going forward.

I am hopeful that AV2 will be an exciting development for the still image world, but the modern Web image compression ecosystem still has some glaring issues. In libaom, tune iq still suffers from consistency issues due to strange encoder decisions that are byproducts of images being second-class to video. Additionally, the fastest libaom preset often requires almost 80% more encoding time than the fastest libwebp preset with a much higher memory footprint.

Potentially the biggest issue of all is that working full-time on community-supported encoders is impossible to justify without compensation, especially when you don't have a clientele that needs strong still image performance.

At Halide Compression, my goal is to fundamentally change these incentives. For many companies, images are highly expensive, and a highly efficient licensable encoder alongside an expert consulting team is a valuable thing. Iris-WebP is already changing the narrative for WebP by providing unprecedented efficiency gains over a reference implementation that is already designed with images in mind. An image-first ecosystem, supported by a dedicated team, becomes necessary to make modern image formats usable.

I hope you enjoyed the read and learned something. If you'd like to talk to me or Halide about my open-source work, Iris, or anything else, shoot us an email! Thanks for reading!